The scientism of obscurantists

Even the most rabid of the antiscience ranters would rather have science on their side

British M.D. Ebenezer Sibly (1751-1799) is a kind of transitional fossil in the history of ideas. His magnum opus, A Key to Physic and the Occult Sciences, published in 1792, is quite up-to-date not only with the scientific facts of his time (he describes blood circulation and even mentions the then-recently discovered oxygen gas), but also with cutting-edge scientific speculation, explaining, for instance, magnetic forces in terms of atoms and the exchange of microscopic particles between iron and lodestone.

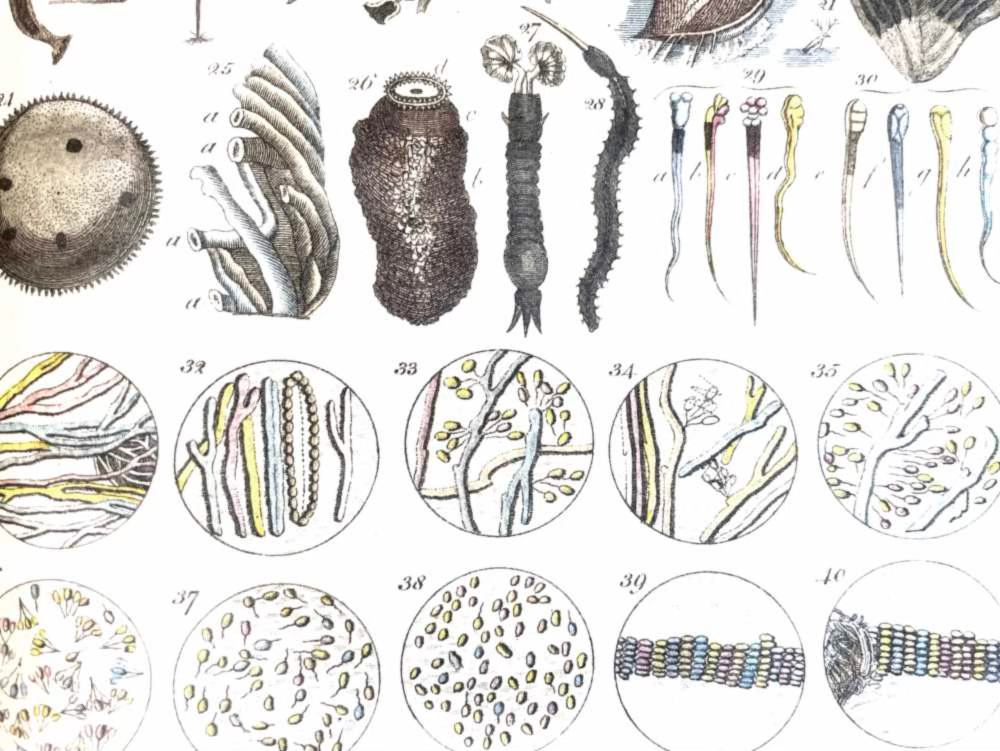

Speaking on microscopic, the book is lavishly illustrated with color plates that include carefully drawn, detailed pictures of microbes and sperm (you can see part of the illustration in the image above). Other plates, however, show a cabalistic map of the Kingdom of Heaven and horoscopes. For him, gravity and magnetism are manifestations of the anima mundi, an all-pervasive soul, emanating from God, that is behind the phenomena of astrology and magic, among several other things.

To Sibly, the existence of the circulatory system proves that, as the Hermetic magicians of Antiquity taught, the human body is a microcosm, a Universe in miniature: the heart being the miniature Sun, and the bladder, the ocean, where the rivers of the microcosm discharge themselves. Dr. Sibly is up-to-date with the science, but for him the most advanced science of his time just confirms, reafirms — and, to a certain extent, illuminates and explains — what astrologers, alchemists, and wizards have known and believed all along.

By the end of the 18th century, Sibly’s mysticism had already become out of touch with the times. Isaac Newton’s obituary, presented to the French Royal Academy of Sciences in 1727 — almost three decades before Sibly’s birth — piously omitted his youthful interest in astrology. That was considered, by then, an unworthy subject for a distinguished man of science, and an absolute embarrassment; to include it in the great Newton’s elegy would’ve been a faux pas. Later, the first edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, from 1771, gave less than a page to “astrology”, but sixty-seven pages to “astronomy”.

But on the other side of the widening gap between science and superstition, Sibly’s strategy prospered. At the same time that science washed its hands of occult speculation, occultists, wizards, esotericists, astrologers, and brazen irrationalists began to claim scientific support for their own eccentricities. Even Joseph de Maistre (1753 – 1821), the great irrationalist mystic and reactionary, for whom skepticism and rationalism were universal acids that would dissolve civilization and reduce men to cannibalism and savagery, felt sure that one day the whole of science would be transformed and come around to the belief that “the old traditions are all true”.

From then on, the “science supports me/agrees with me/is starting to agree with me/one day will prove me right” trope was warmly embraced by every proponent of occultism or esotericism of note, sometimes with a passive-aggressive tint: Helena Blavastky (1831-1891), creator of the most successful and influential esoteric doctrine of the Modern Age, Theosophy, was wont to say that science was just giving its first baby steps into fields her Secret Masters had already trod and fully mapped. However, she was not beyond appropriating scientific ideas and concepts for her own rhetorical ends, like she did with the (now defunct) hypothesis of a sunken continent in the Indian Ocean, Lemuria, which she postulated as the cradle of human evolution.

A little after Blavatsky’s (mis)appropriation of geology and evolutionary theory, Aleister Crowley (1875-1947), “The Great Beast 666”, chose the motto “The Method of Science, The Aim of Religion” for one of his occultist enterprises. Fast forward to the second half of the 20th century, and we find the likes of Gary Zukav, Amit Goswami, Deepak Chopra, and Fritjof Capra swearing that quantum physics has rediscovered truths already established long ago by ascetic yogis and Tibetan monks — truths that supposedly include the power of positive thinking and may even support the validity of astrology.

Zukav once wrote that graduate programs in physics would someday have to include meditation classes. Chopra affirms that, via quantum effects, positive thinking can alter DNA. Goswami invented, among other things, “quantum astrology”.

Historian Olav Hammer refers to this process as “disembedding”, meaning the unmooring of scientific facts, concepts, hypotheses, and jargon from their proper contexts and, what is worse, from the proper scientific ethos of critical evaluation, organized skepticism, and empirical testing. Analogies from science popularization efforts are also disembedded and treated not as metaphors or approximations, but as statements of fact.

The products assembled from all of this disembedding are called, by scholars who research the esoteric and New Age movements, scientism. Of course, the same word also has the non-technical meaning of excessive/undue/exaggerated confidence in the powers and sufficiency of the natural sciences to give a complete, proper account of the world. The high prevalence of scientism (in the New Age scholarship sense) makes it hard to distinguish between modern forms of mysticism and pseudoscience properly.

The reason for all of this, as can be imagined, is the great cultural capital of science, accumulated from Galileo forward. Because science works, its name commands respect. As playwright and Nobel Prize laureate George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950) once quipped, if you wanted people, in the 20th century, to believe stuff that deeply offends common sense, the easiest way would be to call it “scientific”. The same largely applies now in the 21st century, even if “traditional” and “originary” are gaining.

In a better world, people would be educated enough and skeptical enough to see the emptiness (or the scam) behind the abuses of the “science” label. Unfortunately, we are not there yet.